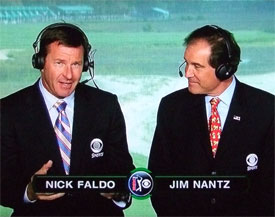

Nearly flawless as a golf announcer, Jim Nantz and his dulcet tone define Masters’ broadcasts for this generation. Nearly flawless . . . his man-crush on former college roomie Fred Couples is a concern, especially as it approaches white-hot intensity every April once Magnolia Lane opens to the patrons. “Back in ’89 when Freddie had that closing 67, we all remember how . . .” No, Jimmy, nobody but you, Freddie, and his caddie remember. But since Freddie is so cool (and good), Mr. Smooth gets a pass on the man-crush. I do have one issue to raise, however, with no forthcoming pass for the Well-Pitched-One. It’s his word choice when he refers, over and again, to his current and distinguished CBS booth partner as Sir Nick Faldo. Really, “Sir”?

Nothing against the six-time major champion and World Golf Hall of Famer, or his fellow Brits. Faldo, as far as this American can tell, deserves the honor of knighthood (received in 2009) as much as any other subject of the British empire. His contributions to the sport and representation of his country merit prominent recognition. I understand that Nantz’s gesture of using his partner’s royally endowed title is done out of respect. And respect, of course, is in the golf etiquette rota.

Let me raise, however, a slight protest – American style. Respect can still be had without stealing a smidge of the Queen’s English. Sir does have proper and common usage in American English when relationships are hierarchical – US military, younger-elder – or when commercial service is rendered. But it is never used as a title, only as a generic address. Sir as title is the propriety of our English cousin-society where the monarchy, booted out of our society in 1776, yet survives.

Jim Nantz is a class act, no question. I don’t mind an initial and respectful acknowledgement of Sir Nick Faldo – one time is sufficient – at the beginning of the broadcast. But, when used over and again . . . does our boy Nantz fancy himself an aristocrat? Hanging out at Augusta National all these years, perhaps so. I don’t hear David Feherty, or any other commentator, calling their CBS colleague Sir Nick on the air. Feherty, a native of Northern Ireland, became a U.S. citizen in 2010. He understands his adopted country’s history, in this particular area, perhaps a bit better than the lead announcer.

Want to read on? The front side was pretty easy . . . back side tougher!

Here’s a word (I’m surprised to find out) with which many Americans are unfamiliar: egalitarianism. Along with the ever-popular liberty, egalitarianism is a founding principle of American society. Egalitarianism is shown forth by Thomas Jefferson’s statement in the Declaration of Independence “All men (sic) are created equal.” Egalitarianism does not refer to equal distribution of goods, per se; it refers to equal status and worth, socially and politically, accorded to all. Favoritism via gender, race, family name, or inherited wealth be damned! America is the land where oversized concentrations of power – whether it be a king, an overzealous military general, or a business titan – are kept in check. That is egalitarianism, and it’s American as apple pie.

The last thirty-five years have seen a steep rise in social and income inequality in the United States. In my book, Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good, I refer to the current time period as one of three recent short eras of excess. (The other two are the Gilded Age of late 19th century and the Roaring ’20s.) Like a pendulum that swings back and forth, American society has oscillated between eras of excess and relative equality. Said so well by Gilded Age critic Henry Demarest Lloyd: “Liberty produces wealth, and wealth destroys liberty.” Egalitarianism and liberty have worked together in this society to balance out the other’s excesses. Too much liberty exacerbates inequalities. Too much egalitarianism stifles creativity and growth. Eras of excess are a throwback, essentially, to the days and societies of an earlier Europe that many of our ancestors, with no chance to improve their economic or social status, left behind.

American society, where previously only white property owners had the vote, has struggled with what egalitarianism and liberty have meant for all of its inhabitants: indigenous, slaves, women, children, immigrants, and minorities. Today the struggle continues for what these two foundational principles mean for gays. Egalitarianism and liberty together are the proper form in our society. Relative balance, as evidenced in Nick Faldo’s swing when in his prime, holds it all together.

Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good is available at the Blue Ocotillo Publishing website. Thanks for joining me for this outing!